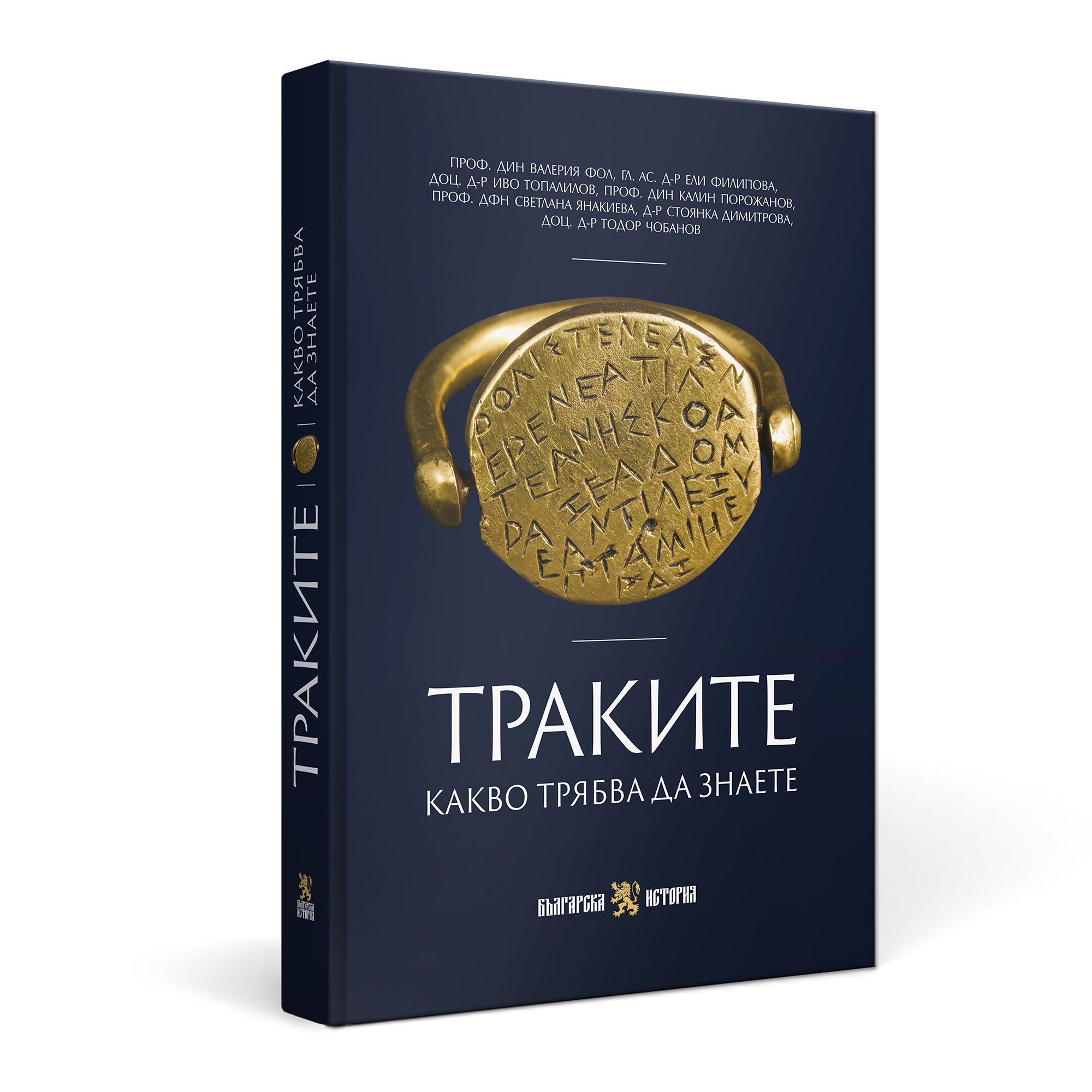

This book The Thracians: What You Need to Know written by Valeria Fol, Eli Filipova, Ivo Topalilov, Kalin Porozhanov, Svetlana Yanakieva, Stoyanka Dimitrova and Todor Chobanov appears to have been conceived for a general audience, aiming to present the complexities of Thracian studies in an accessible format for readers without prior training. It is authored by a team of scholars from the Institute of Balkan Studies with the Centre of Thracology at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences in Sofia.

In terms of content, the book includes a preface, twenty distinct sections on specific aspects of Thracian history, a glossary, a bibliography, information about the authors, and illustrations.

The preface outlines the purpose of the publication: to provide answers to fundamental questions in Thracian history, including: Who were the Thracians? Where did they come from? How did they live, and what did they believe? Who were their rulers, and what were their kingdoms? What was their language? and others.

The main part of the book begins with a (perhaps too brief) discussion of the sources used to reconstruct Thracian history and the methodology employed, referred to as Interpraetatio Thracica. The formation of Thracian ethnicity is then discussed, though with similar brevity.

One section focuses on the Thracian language, briefly covering glosses, inscriptions, onomastics, and the language’s characteristics and spread. More attention could have been given to the famous inscription from the Sanctuary of Apollo at Zone, which is considered the longest known text in the Thracian language. Notably, this inscription appears on the same stone as a Greek public inscription. Closely related to the language issue is the following section, which juxtaposes the Thracians with the Pelasgians.

The next three sections examine early Thracian political history, including their participation in the Trojan War, the characteristics of the Thracian tribes, and the Greek colonization of the Thracian coasts.

The book continues with an ethnographic overview of the Thracians, exploring the natural characteristics of the lands they inhabited, their lifestyle, settlements, and social structure, with a particular focus on kingship and royal power.

A separate section is devoted to the political centers of the Thracian kingdoms, concentrating on the Getae, Triballians, and Odrysians. Logically, the Odrysian kingdom receives the most attention, as it is the best-documented and most studied state structure of the Thracians.

The next two sections are interconnected, covering Thracian art – especially treasures – and Thracian religion, offering an overview of deities, rituals, and cult sites.

Three sections continue the exploration of political history, examining key moments in the Thracian lands during the reigns of Philip II and Alexander III, the Celtic invasions, and the state of Cavarus. Although the next chapter’s title refers to the fall of Thrace under Roman rule, it does not discuss the Roman campaigns in Thrace. Instead, it focuses on events during and after the reign of Augustus.

Special attention is given to the so-called Northern Thracians, with subsections on the Krobyzoi and Terizi, Getae, Triballians, and Dacians. There is some repetition regarding the Getae and the Triballians, who are also covered in the section on Thracian political centers.

Following this, the book discusses the Thracians’ role in the administrative life of the Roman province of Thrace and the broader empire, their Christianization, the barbarian invasions in the Balkans during late antiquity, and the fate of the Thracians in the Middle Ages. The final section addresses Thracian cultural heritage in contemporary folklore.

The glossary clarifies some of the more specific terms used in the text. However, the absence of a chronological table makes it difficult for readers to grasp the broader timeline of Thracian history. Including one in a future edition would be beneficial.

The selection criteria for the images at the end of the book are unclear. They are few in number, inconsistently numbered, and the maps lack uniformity.

In any case, the book achieves its primary goal – giving answers to a number of questions on the Thracians and introducing readers to various aspects of Thracian history. It avoids sensationalism and, in some ways, could even be described as overly conservative, which has its merits. However, given the vast range of topics covered, experts in the field may have their own critiques regarding the book’s structure, comprehensiveness, opinions expressed, and the completeness of the bibliography. The authors would do well to consider an English edition in order to reach a wider audience.

Jordan Iliev, PhD, National Centre for Information and Documentation, Sofia